Pokemon is arguably one of the most popular and widely recognized Role-playing games in the world, which is quite a feat for a genre with relatively low sales. Its addictive monster-catching gameplay is by no means revolutionary, but it is bolstered by an approachable battle system and strong core mechanics that have more or less endured the span of twenty years through the introduction of additional wrinkles. For newcomers, these can be seen as a gimmick- something new that appears in each new generation that may appear frequently during the course of a playthrough. For high-level and professional players, they are aspects that define and shape the competitive metagame based on their permanence- or lack thereof, if you consider the weather wars of generation five.

One aspect where Pokemon has never truly excelled, however, is in its narratives. In the earlier generations of the franchise, this could be excused by technical limitations and the amount of localization that needed to go into every other aspect of the core mechanics. The result were simplistic narratives with an occasional antagonistic force, but an ultimate goal of reaching and defeating the Elite Four of each respective region, crowning the player as champion, an unrivaled individual in the mythos. In many ways, these champions were the most iconic aspect of each narrative- from the last rival battle of generation one, to the powerhouse champion of generation four. The revelation of the previous Pokemon trainer from generation one as the final challenge of generation two left quite an impression- perhaps he did not use the same Pokemon as the player did when they completed that game, but the overarching goal of the series is to catch every Pokemon- and so Red's stacked team of starters and iconic generation one Pokemon only makes sense, as do their impressive levels.

Although generation three and four would dabble in more intense extremes with their legendary Pokemon- with generation four introducing what is largely considered to be the closest equivalent to a god that the series has- these creatures were always conquerable through the player's actions to thwart the antagonist team of each narrative, or through their desire to catch every last Pokemon in the game. There was context as to how these Pokemon were summoned, but the only way they could be controlled was by defeating them in a good old fashioned Pokemon battle. This, and the idea of defeating five of the highest level trainers in a region without stopping, were incentive enough for players to feel empowered and satisfied with each entry. This must be so, as the series would not be where it is today without four generations of this formula.

Yet, with the onset of the fifth generation as some of the last major releases on the Nintendo DS, there came something of a shift. Pokemon Black and White were what could be considered the first genuinely narrative-driven Pokemon, as almost every town and city in the game featured some sort of event dealing with the antagonistic force, Team Plasma, and the goal of the game was not only to defeat the Elite Four and its champion, but also to stop a character who was, in many ways, similar to the playable character of each previous generation. N's possession of a legendary Pokemon put him above any other Pokemon trainer in the game, and in the final moments before challenging him, the player awakens their own legendary Pokemon to catch and use against him.

While this storyline was far from complex, featuring only one real twist at its conclusion, it did mark a change for the series that would worsen over time. N was, in many ways, a more important character to the mythos of generation five than the playable character themselves. That he returned to play a key role in the sequel titles, Pokemon Black 2 and Pokemon White 2, was more than proof of this. The passage of time that took place during this extended narrative was further evidence that the player's own actions had very little sway in determining the outcome of these titles. What is more disappointing, however, is that the protagonists of the original Black and White never returned in these games to challenge the player as they did in Pokemon Gold and Silver, which are titles that play much more like a true sequel to the previous generation than any others in the series. The increased focus on narrative and the importance of non-playable characters in each subsequent title is something of a surprising turn, as it creates a sort of tonal dissonance that never seemed to appear in the titles where dialogue and narrative, and presentation were simpler. With Game Freak's attempts to make each title more compelling from an aesthetic and cinematic perspective, they have strayed from the general appeal of the games, which is the idea of surmounting other trainers and catching more Pokemon.

While this storyline was far from complex, featuring only one real twist at its conclusion, it did mark a change for the series that would worsen over time. N was, in many ways, a more important character to the mythos of generation five than the playable character themselves. That he returned to play a key role in the sequel titles, Pokemon Black 2 and Pokemon White 2, was more than proof of this. The passage of time that took place during this extended narrative was further evidence that the player's own actions had very little sway in determining the outcome of these titles. What is more disappointing, however, is that the protagonists of the original Black and White never returned in these games to challenge the player as they did in Pokemon Gold and Silver, which are titles that play much more like a true sequel to the previous generation than any others in the series. The increased focus on narrative and the importance of non-playable characters in each subsequent title is something of a surprising turn, as it creates a sort of tonal dissonance that never seemed to appear in the titles where dialogue and narrative, and presentation were simpler. With Game Freak's attempts to make each title more compelling from an aesthetic and cinematic perspective, they have strayed from the general appeal of the games, which is the idea of surmounting other trainers and catching more Pokemon.

(USA)_(E)-8.png) The very nature of Pokemon is ridiculous: people using their pets to fight with elemental attacks until one side is able to literally knock out the other, after which the combatants dole out prize money and the loser becomes so paralyzed with fear that they never leave their spot for the rest of their lives. That last part may sound particularly silly, but when thinking of these games in context, the only person who never truly loses is you, the player. This says more about your ambition and determination to win than anything else, and it is something that is communicated perfectly fine via gameplay, not narrative. However, the Pokemon titles have increasingly relied on having rival friends, trainers, and most egregiously characters that are key to the narrative be affected by the way you play the game, which is unwarranted because the player character has absolutely no character. They are meant to be an extension of the player, and the player may or may not care about the particular feelings of each member of the Pokemon narrative, but they have no option to affect the way the narrative progresses in any manner.

The very nature of Pokemon is ridiculous: people using their pets to fight with elemental attacks until one side is able to literally knock out the other, after which the combatants dole out prize money and the loser becomes so paralyzed with fear that they never leave their spot for the rest of their lives. That last part may sound particularly silly, but when thinking of these games in context, the only person who never truly loses is you, the player. This says more about your ambition and determination to win than anything else, and it is something that is communicated perfectly fine via gameplay, not narrative. However, the Pokemon titles have increasingly relied on having rival friends, trainers, and most egregiously characters that are key to the narrative be affected by the way you play the game, which is unwarranted because the player character has absolutely no character. They are meant to be an extension of the player, and the player may or may not care about the particular feelings of each member of the Pokemon narrative, but they have no option to affect the way the narrative progresses in any manner.

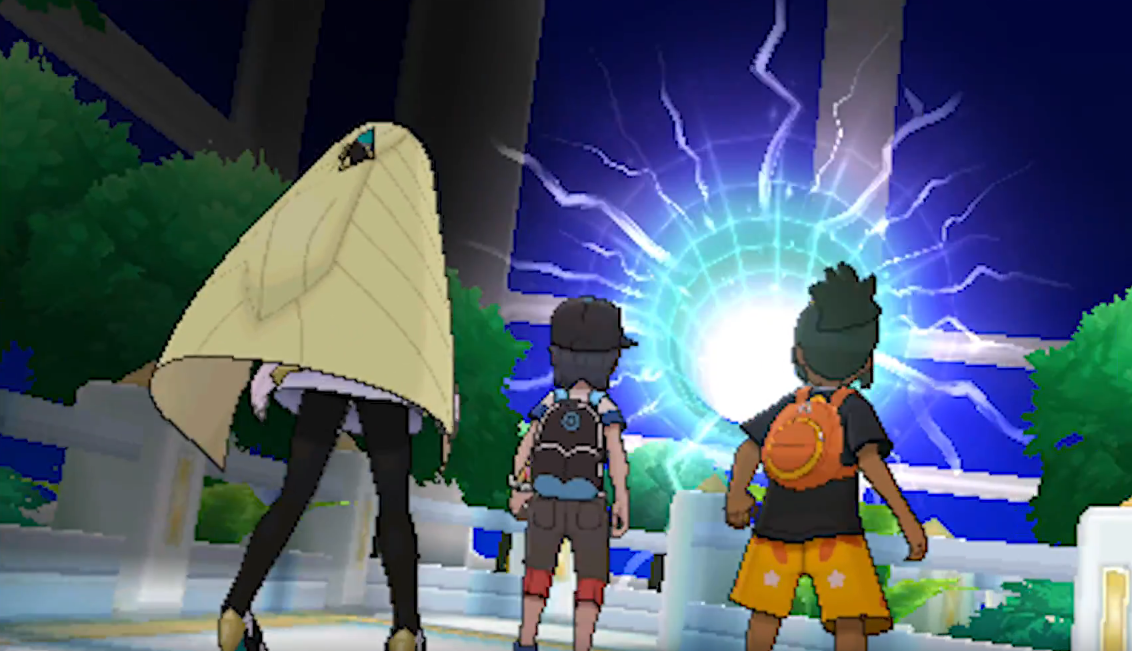

This is further complicated by the oddities that Game Freak has added with each new installment of the franchise. The momentum shift that took place between generation two and four, during which legendary Pokemon went from being guardians and territorial creatures to godlike manipulators of the planet and fabric of time and space itself, was wild enough in its own right. Following the revelation of a godlike Pokemon, however, Game Freak has instead attempted to scale back the dominance angle of each legendary Pokemon while simultaneously increasing their destructive potential. Every trainer in Unova must bow to N because he is in possession of a legendary Pokemon and able to defeat the Elite Four. A mysterious three-thousand year old man murdered thousands of Pokemon in order to grant his stupid Fairy Pokemon eternal life. A woman is driven to the point of insanity after encountering hyper-dimensional Pokemon and abuses her children and resources in order to travel to their place of origin. While Pokemon has featured acts of terrorism and abuse of its titular monsters throughout the franchise, the balance between nature and humanity was often the catalyst and motivation for the player to intervene. For a game that is more or less aimed at children, this seems a more sensible route- clearly defined good and evil sides, simplistic relationships and motivations.

However, as the Pokemon franchise has matured, so have its attempts to add new ideas to its mythology, and though once this mythology was largely based on the legendary might of the Pokemon themselves, a human element has become greater and greater despite the level of interactivity on the player's part remaining relatively the same. While many role-playing games would use dialogue options, side-quests, and branching narratives in order to achieve the effect of a player embracing a character- or, perhaps, playing a role- Pokemon has almost none of this. And sure, one could argue it is because there's enough time spent attempting to create the geography of a region and inserting logical Pokemon into these specific environments- except, the narratives of these games have become less about the harmonious relationship between Pokemon and humans and more about humanity attempting to cope with the insane amounts of power and influence that Pokemon have over the world as a whole.

The truth is, if Pokemon were a franchise that attempted to mature in a tonal sense, these storylines would feel justified. If Pokemon attempted to achieve any aspect of narrative cohesion between titles, this might also be justified. Pokemon Gold, Silver, and Crystal are a rare exception in the series as they allow players not only to explore a new region that adds to the mythology, but they are also given the opportunity to return to the region of the previous generation and witness the changes that they themselves enacted over the course of the previous generation. This leads to a sense of empowerment in a greater scope, and the anticipation of knowing that their previous player character is out in the world and presents a challenge adds another level of immersion that players still reflect upon fondly to this day. This is a complex relationship for a player, and even a player character, to have within a game world, but it is executed with far less text and narrative bloat than what is present in more recent titles.

The main issue here, of course, is that Game Freak has no logical reason to change their course of action. Pokemon titles continue to make massive profit, and the core mechanics of the game remain intact so that they have little to truly iterate upon, except with contextual layers atop said formula that, until recently, were universal and non-contextual, until they decided to add luau dances to a battle mechanic. There are, however, a number of titles that exist which are able to achieve what Pokemon fails to do: Pokemon Mystery Dungeon has extremely similar core mechanics, but its more absurd concept allows for deeper and arguably more emotional storylines. Shin Megami Tensei has much more disturbing implications about the relationship between humans and their catch-able demons, and features morality and dialogue systems that give more agency of choice to the player. Dragon Quest Monsters focuses on vignette scenarios that require little context in order to be approachable as well as its own set of clearly defined core mechanics. Digimon offers more dialogue and intrigue it its narratives because it has fewer dedicated fans to piss off, as well as branching evolution paths. Spectrobes is a godlike amalgamation of all of the best elements of the previously-mentioned titles. Okay, that last one is a lie. Spectrobes is nothing like any of the other games, but its still fun.

With Pokemon, the shift towards more story-driven content seems to have been made out of the desire to please fans who bemoan each title's similarity. By introducing more and more ridiculous narrative folds and concepts, they are able to offer more variety, certainly, but it remains wrapped in a sugar coating that fails to respect seasoned players while further disconnecting the player from their in-game avatar. An almost nauseating phrase comes to mind, but it needs to be said: you can't have your cake and eat it, too. Over-complicating character relationships and personalities means nothing if the player has no real sway in the narrative. You cannot present these complex ideas in a simplistic manner when you already have an extremely compelling means of creating organic storytelling. That method, of course, is the catch-able nature of Pokemon themselves. Players must balance type combinations, encounter rates, movesets, resources, and more into their experience traveling the world, so turning said world into a series of cutscene-laden concrete paths with shoulders of wild grass does little to mitigate the feeling of genuine excitement that accompanies finding a new Pokemon or an old favorite. But, these pleas will most certainly fall on deaf ears, for although Game Freak has done a great deal in attempting to complicate what is a simple premise, they have done little to act upon or even maintain what their fans would like.

Which means, it is time to start being a Shin Megami Tensei fan, instead.

Do you think Pokemon narratives have become to complex for their own good? Do you wish Pokemon had more content than just "catch Poke, train Poke, beat trainer, buy clothes?" Do you think this article is bullshit? As always, we encourage feedback and discussion, so feel free to leave a comment, subscribe for more content, or share with friends. This article is part of an ongoing analysis of RPG narratives during the month of May. Stay tuned for more on the subject.

One aspect where Pokemon has never truly excelled, however, is in its narratives. In the earlier generations of the franchise, this could be excused by technical limitations and the amount of localization that needed to go into every other aspect of the core mechanics. The result were simplistic narratives with an occasional antagonistic force, but an ultimate goal of reaching and defeating the Elite Four of each respective region, crowning the player as champion, an unrivaled individual in the mythos. In many ways, these champions were the most iconic aspect of each narrative- from the last rival battle of generation one, to the powerhouse champion of generation four. The revelation of the previous Pokemon trainer from generation one as the final challenge of generation two left quite an impression- perhaps he did not use the same Pokemon as the player did when they completed that game, but the overarching goal of the series is to catch every Pokemon- and so Red's stacked team of starters and iconic generation one Pokemon only makes sense, as do their impressive levels.

Although generation three and four would dabble in more intense extremes with their legendary Pokemon- with generation four introducing what is largely considered to be the closest equivalent to a god that the series has- these creatures were always conquerable through the player's actions to thwart the antagonist team of each narrative, or through their desire to catch every last Pokemon in the game. There was context as to how these Pokemon were summoned, but the only way they could be controlled was by defeating them in a good old fashioned Pokemon battle. This, and the idea of defeating five of the highest level trainers in a region without stopping, were incentive enough for players to feel empowered and satisfied with each entry. This must be so, as the series would not be where it is today without four generations of this formula.

Yet, with the onset of the fifth generation as some of the last major releases on the Nintendo DS, there came something of a shift. Pokemon Black and White were what could be considered the first genuinely narrative-driven Pokemon, as almost every town and city in the game featured some sort of event dealing with the antagonistic force, Team Plasma, and the goal of the game was not only to defeat the Elite Four and its champion, but also to stop a character who was, in many ways, similar to the playable character of each previous generation. N's possession of a legendary Pokemon put him above any other Pokemon trainer in the game, and in the final moments before challenging him, the player awakens their own legendary Pokemon to catch and use against him.

While this storyline was far from complex, featuring only one real twist at its conclusion, it did mark a change for the series that would worsen over time. N was, in many ways, a more important character to the mythos of generation five than the playable character themselves. That he returned to play a key role in the sequel titles, Pokemon Black 2 and Pokemon White 2, was more than proof of this. The passage of time that took place during this extended narrative was further evidence that the player's own actions had very little sway in determining the outcome of these titles. What is more disappointing, however, is that the protagonists of the original Black and White never returned in these games to challenge the player as they did in Pokemon Gold and Silver, which are titles that play much more like a true sequel to the previous generation than any others in the series. The increased focus on narrative and the importance of non-playable characters in each subsequent title is something of a surprising turn, as it creates a sort of tonal dissonance that never seemed to appear in the titles where dialogue and narrative, and presentation were simpler. With Game Freak's attempts to make each title more compelling from an aesthetic and cinematic perspective, they have strayed from the general appeal of the games, which is the idea of surmounting other trainers and catching more Pokemon.

While this storyline was far from complex, featuring only one real twist at its conclusion, it did mark a change for the series that would worsen over time. N was, in many ways, a more important character to the mythos of generation five than the playable character themselves. That he returned to play a key role in the sequel titles, Pokemon Black 2 and Pokemon White 2, was more than proof of this. The passage of time that took place during this extended narrative was further evidence that the player's own actions had very little sway in determining the outcome of these titles. What is more disappointing, however, is that the protagonists of the original Black and White never returned in these games to challenge the player as they did in Pokemon Gold and Silver, which are titles that play much more like a true sequel to the previous generation than any others in the series. The increased focus on narrative and the importance of non-playable characters in each subsequent title is something of a surprising turn, as it creates a sort of tonal dissonance that never seemed to appear in the titles where dialogue and narrative, and presentation were simpler. With Game Freak's attempts to make each title more compelling from an aesthetic and cinematic perspective, they have strayed from the general appeal of the games, which is the idea of surmounting other trainers and catching more Pokemon.(USA)_(E)-8.png) The very nature of Pokemon is ridiculous: people using their pets to fight with elemental attacks until one side is able to literally knock out the other, after which the combatants dole out prize money and the loser becomes so paralyzed with fear that they never leave their spot for the rest of their lives. That last part may sound particularly silly, but when thinking of these games in context, the only person who never truly loses is you, the player. This says more about your ambition and determination to win than anything else, and it is something that is communicated perfectly fine via gameplay, not narrative. However, the Pokemon titles have increasingly relied on having rival friends, trainers, and most egregiously characters that are key to the narrative be affected by the way you play the game, which is unwarranted because the player character has absolutely no character. They are meant to be an extension of the player, and the player may or may not care about the particular feelings of each member of the Pokemon narrative, but they have no option to affect the way the narrative progresses in any manner.

The very nature of Pokemon is ridiculous: people using their pets to fight with elemental attacks until one side is able to literally knock out the other, after which the combatants dole out prize money and the loser becomes so paralyzed with fear that they never leave their spot for the rest of their lives. That last part may sound particularly silly, but when thinking of these games in context, the only person who never truly loses is you, the player. This says more about your ambition and determination to win than anything else, and it is something that is communicated perfectly fine via gameplay, not narrative. However, the Pokemon titles have increasingly relied on having rival friends, trainers, and most egregiously characters that are key to the narrative be affected by the way you play the game, which is unwarranted because the player character has absolutely no character. They are meant to be an extension of the player, and the player may or may not care about the particular feelings of each member of the Pokemon narrative, but they have no option to affect the way the narrative progresses in any manner.This is further complicated by the oddities that Game Freak has added with each new installment of the franchise. The momentum shift that took place between generation two and four, during which legendary Pokemon went from being guardians and territorial creatures to godlike manipulators of the planet and fabric of time and space itself, was wild enough in its own right. Following the revelation of a godlike Pokemon, however, Game Freak has instead attempted to scale back the dominance angle of each legendary Pokemon while simultaneously increasing their destructive potential. Every trainer in Unova must bow to N because he is in possession of a legendary Pokemon and able to defeat the Elite Four. A mysterious three-thousand year old man murdered thousands of Pokemon in order to grant his stupid Fairy Pokemon eternal life. A woman is driven to the point of insanity after encountering hyper-dimensional Pokemon and abuses her children and resources in order to travel to their place of origin. While Pokemon has featured acts of terrorism and abuse of its titular monsters throughout the franchise, the balance between nature and humanity was often the catalyst and motivation for the player to intervene. For a game that is more or less aimed at children, this seems a more sensible route- clearly defined good and evil sides, simplistic relationships and motivations.

However, as the Pokemon franchise has matured, so have its attempts to add new ideas to its mythology, and though once this mythology was largely based on the legendary might of the Pokemon themselves, a human element has become greater and greater despite the level of interactivity on the player's part remaining relatively the same. While many role-playing games would use dialogue options, side-quests, and branching narratives in order to achieve the effect of a player embracing a character- or, perhaps, playing a role- Pokemon has almost none of this. And sure, one could argue it is because there's enough time spent attempting to create the geography of a region and inserting logical Pokemon into these specific environments- except, the narratives of these games have become less about the harmonious relationship between Pokemon and humans and more about humanity attempting to cope with the insane amounts of power and influence that Pokemon have over the world as a whole.

The truth is, if Pokemon were a franchise that attempted to mature in a tonal sense, these storylines would feel justified. If Pokemon attempted to achieve any aspect of narrative cohesion between titles, this might also be justified. Pokemon Gold, Silver, and Crystal are a rare exception in the series as they allow players not only to explore a new region that adds to the mythology, but they are also given the opportunity to return to the region of the previous generation and witness the changes that they themselves enacted over the course of the previous generation. This leads to a sense of empowerment in a greater scope, and the anticipation of knowing that their previous player character is out in the world and presents a challenge adds another level of immersion that players still reflect upon fondly to this day. This is a complex relationship for a player, and even a player character, to have within a game world, but it is executed with far less text and narrative bloat than what is present in more recent titles.

The main issue here, of course, is that Game Freak has no logical reason to change their course of action. Pokemon titles continue to make massive profit, and the core mechanics of the game remain intact so that they have little to truly iterate upon, except with contextual layers atop said formula that, until recently, were universal and non-contextual, until they decided to add luau dances to a battle mechanic. There are, however, a number of titles that exist which are able to achieve what Pokemon fails to do: Pokemon Mystery Dungeon has extremely similar core mechanics, but its more absurd concept allows for deeper and arguably more emotional storylines. Shin Megami Tensei has much more disturbing implications about the relationship between humans and their catch-able demons, and features morality and dialogue systems that give more agency of choice to the player. Dragon Quest Monsters focuses on vignette scenarios that require little context in order to be approachable as well as its own set of clearly defined core mechanics. Digimon offers more dialogue and intrigue it its narratives because it has fewer dedicated fans to piss off, as well as branching evolution paths. Spectrobes is a godlike amalgamation of all of the best elements of the previously-mentioned titles. Okay, that last one is a lie. Spectrobes is nothing like any of the other games, but its still fun.

With Pokemon, the shift towards more story-driven content seems to have been made out of the desire to please fans who bemoan each title's similarity. By introducing more and more ridiculous narrative folds and concepts, they are able to offer more variety, certainly, but it remains wrapped in a sugar coating that fails to respect seasoned players while further disconnecting the player from their in-game avatar. An almost nauseating phrase comes to mind, but it needs to be said: you can't have your cake and eat it, too. Over-complicating character relationships and personalities means nothing if the player has no real sway in the narrative. You cannot present these complex ideas in a simplistic manner when you already have an extremely compelling means of creating organic storytelling. That method, of course, is the catch-able nature of Pokemon themselves. Players must balance type combinations, encounter rates, movesets, resources, and more into their experience traveling the world, so turning said world into a series of cutscene-laden concrete paths with shoulders of wild grass does little to mitigate the feeling of genuine excitement that accompanies finding a new Pokemon or an old favorite. But, these pleas will most certainly fall on deaf ears, for although Game Freak has done a great deal in attempting to complicate what is a simple premise, they have done little to act upon or even maintain what their fans would like.

Which means, it is time to start being a Shin Megami Tensei fan, instead.

Do you think Pokemon narratives have become to complex for their own good? Do you wish Pokemon had more content than just "catch Poke, train Poke, beat trainer, buy clothes?" Do you think this article is bullshit? As always, we encourage feedback and discussion, so feel free to leave a comment, subscribe for more content, or share with friends. This article is part of an ongoing analysis of RPG narratives during the month of May. Stay tuned for more on the subject.

Comments

Post a Comment