Video games have evolved in ways previously thought impossible since

their inception, largely thanks to the rapid growth and improvement

found in iterative hardware and the importance of such devices in the

digital era. What was once a rudimentary open-world game like The Legend

of Zelda pales in comparison with Breath of the Wild, both games

offering freedom and exploration in vastly different ways. Because of

the rapidly-changing standards, however, titles that were once

considered the highest quality of their era are constantly challenged by

newer efforts. What was once hailed as revolutionary is now considered a

relic, usually only in terms of aesthetic, nothing more. So when

developers claim that they are attempting to evoke a "classic" feeling,

what are we to expect from their product? It isn't necessarily the same

as what is "retro," which, depending one your tendencies, is anything

produced within the previous fifteen to twenty years. As mentioned

elsewhere, utilizing "retro" as a descriptor means the creator is being

consciously derivative of a previous work. On the other hand, a classic

is usually a product that has been evaluated by the populous for an

extended period of time, eventually concluding that the item in question

is a landmark, or exceptional example of its kind.

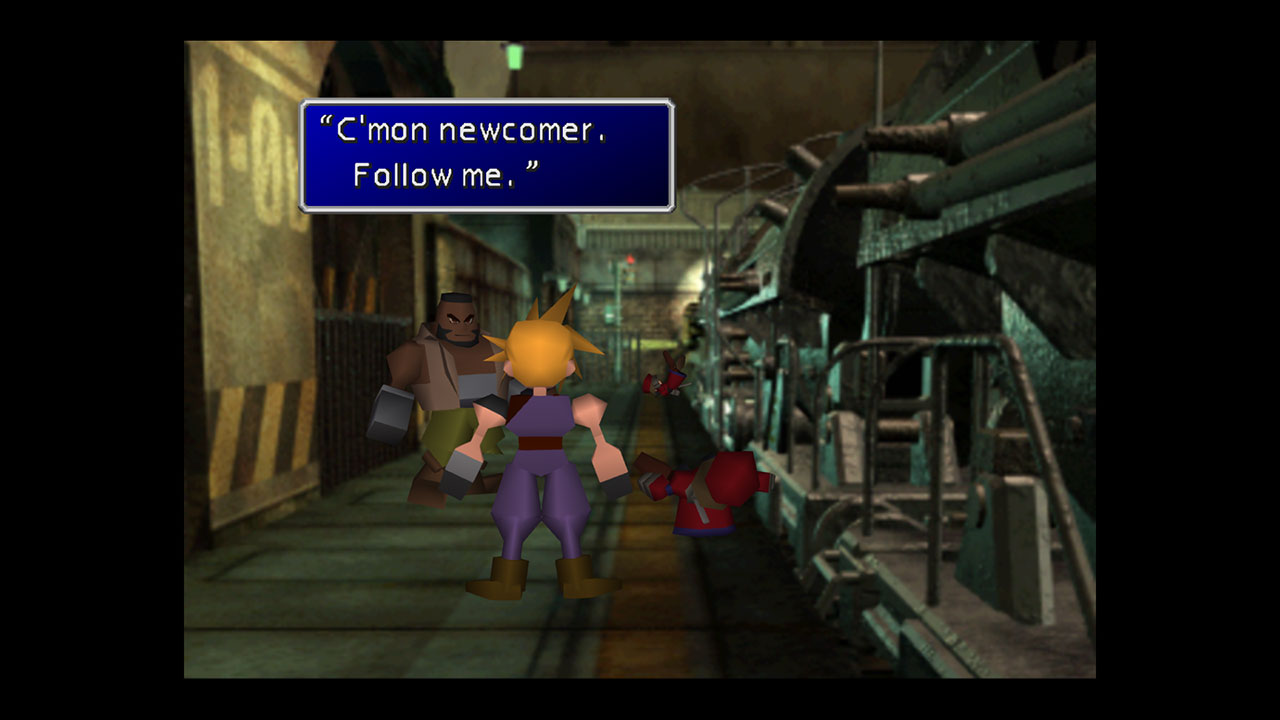

While the terms classic and retro can be applied to a variety of different kinds of media, they take on a different implication in the world of video games. Because of the medium's relative infancy in comparison with other forms of artistic expression and its heavily commercialized nature, it can be difficult to consider any game in specific a classic in the traditional sense. We do tend to favor titles that broke new ground in particular ways, however- whether it is Super Mario 64's platforming physics and freedom of movement, Dragon Quest's success at translating Dungeons and Dragons' role-playing character progression into digital format, or Pong's pong-ness. However, the word classic has also been applied to a number of titles that have received near-universal praise from games' journalists, such as Final Fantasy VII, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and Shadow the Hedgehog. These games were not only considered superb examples of their respective genres upon release, but they have stood the test of time in some way, shape, or form over the years. Sure, Final Fantasy VII's graphics were marvelous during their era, but it is the narrative structure and tried and true action turn-based combat that remain enjoyable. In an ideal perspective of legitimate critique, games should remain timeless because of their gameplay, which avoids growing tiresome by remaining either in-step with, or as compelling as modern standards.

However, because audiences have varied over each respective console generation, it is important to place these titles into historical context. Final Fantasy VI has arguably just as spectacular narrative as the next subsequent title, but one features a refined 16-bit design while the other was an experimental title that made a large splash in the West, birthing an entire generation of Role-playing genre fans. Does this diminish the quality of the former title? Not exactly, and one could argue that both are classics in their own respects- at least, within the terms of the medium. This is the issue with claiming to hearken back to classics, however: many of the ideas present in landmark, iconic installments are often integrated into the fundamentals of their genre. The ATB systems of Final Fantasy VI and VII are built upon the foundations of the fourth entry, which was the first to take bold steps forward in terms of colorful narratives. While gameplay mechanics and quality of life additions are constantly integrated into new titles, the only thing that remains consistent about these classics are their aesthetics and impact at the time. If we seek to glorify these older games through gameplay alone, the product may not differ much from a modern title. Should we attempt to extend the concept to aesthetics and the style of game, well, that is where "retro" enters the field and complicates things further.

In terms of commercial chronology, the term retro can be applied quite literally. Retro games are those with an original street release date at least fifteen years before the current day- certain groups tend to refer to specific hardware generations as retro instead, however. Although many of these titles have seen re-releases on modern hardware, they are a product of the era in which they were developed, and represent the trends and design tendencies of the era. Remakes of a particular title using HD art assets or entirely new models and designs meant to evoke the feel of the original do not fall under this category, however, especially if they include new content. What may complicate this idea further is that some ports are straightforward, while others include additional content that is based on the same aesthetic, gameplay, and game progression. However, these are updated versions of retro titles and must be treated as such.

A retro-inspired or retro-styled game is often referred to as such because it aims not only to recapture a certain gameplay or genre style, but also a retro aesthetic. Most frequently in the case of retro games, a pixel-art aesthetic is usually used to evoke an older feeling, though many retro-styled games have also begun to adopt the aesthetic of 90's PC era polygonal modeling. More often than not, however, retro-styled games are aiming to encompass the feeling of a particular series or genre. No better example would be Yacht Club Games' Shovel Knight, which is touted to have a "8-bit retro aesthetic" on its Kickstarter campaign, although the very same paragraph states that Shovel Knight may remind a player of "Mega Man, Castlevania, or Dark Souls." Its reliance on a "Knight" motif as well as the titular character's blue appearance seem to imply a heavier inspiration from the first of those three, although specific bells and whistles have been added to make for an experience mindful of its heritage yet designed for modern sensibilities.

Shovel Knight may feature some mechanics that have been seen before, such as the DuckTales' iconic cane bounce, but it simply utilizes the formula of older titles to create something new and fresh. Whether or not the positive reception towards the title is based on nostalgic recollections or the game's own quality may still be up for debate, but Shovel Knight is a well-designed title that has its own identity. So is Mutant Mudds, a Renegade Kid/Atooi platformer that features what designer Jools Watsham considers a "12-bit" aesthetic. Whereas Yacht Club painstakingly adhered to the NES 8-bit color palette and animation count and even utilized music composed on similar sound chips, Watsham plays his references a bit more fast and loose, with special stages adopting color palettes evocative of the original Game Boy and Virtual Boy screens. Though both games have references to their gaming heritage, Mutant Mudds only utilizes the "plane-shifting" mechanic from Virtual Boy Wario Land as a core mechanic, its game play and progression more unique in comparison. Although the sequel would eventually utilize boss-battle mechanics, Mutant Mudds features few direct references to retro titles, instead fitting the title of a pixel-aesthetic platformer more than anything else.

The thing about retro-styled games is that, in actuality, almost all games made by smaller studios must rely on creating a more simplistic product by utilizing retro- or at least more simplistic- art assets and gameplay foundations in order to make a profit. Therefore, despite their best efforts, a game that features less complexity ends up feeling more retro by nature. Shovel Knight may do its best to recreate the NES spirit, but its difficulty scaling systems and dialogue are much more modern in nature. Mutant Mudds may have aesthetic throwbacks to prior hardware but its gameplay is unique in comparison. Titles like Ansimuz Games' Elliot Quest draw inspiration from titles like Zelda II and feature pixel-based art, but the inconsistency in basic pixel size is a modern concept that wouldn't have appeared in an NES title. Does this mean they don't stand up to the classics? Of course not- they are informed by their predecessors, but they are able to take liberties in new and exciting ways.

What if a game makes a direct claim to have taken inspiration from such classics, then? This is the more concerning of the two descriptors, as the term classic once again is nebulous by nature. Video games are dubbed classic by nostalgic reflection, as no game has truly stood a marginal test of time. They are classic by the definition of the media that surrounds them, one based heavily on the concept of consumerism and an era where controversy exists in far different forms than, say, those in which great works of literature were published and distributed. To claim that a game takes inspiration from classic Role-playing games, as Tokyo RPG Factory has done with their mission statement and two best-known titles I Am Setsuna and Lost Sphear, is more of a disservice to the product than anything else. In a sense, the typical definition of retro can be applied here, instead: a conscious decision to be derivative. To aspire towards something that, whether or not it is of a high standard, was a product of limited hardware that developers strove to push to the extremes in order to create a product of high quality. The intention to honor those titles is appreciated, but the mission is short-sighted and relatively limited in scope.Ultimately, in attempting to be like a classic, a game loses some of its own identity.

Though iconic titles do exist and there are undoubtedly widely accepted examples of quality, games exist in an accelerated state of proliferation, where communication has increased and services allow for greater exposure, resulting in quality products falling by the wayside in a digital sea. While there are also examples of games that have garnered cult followings, that concept has a different meaning in an age of connectivity, and we have yet to see the effects of such followings outside of crowd-funded titles. (Those are a whole can of worms, themselves.) If there is anything to take from this overly long tirade, however, it is this: as we aspire towards deeper critical analysis and appreciation of video games as an artistic medium, we don't necessarily need to use either "retro" or "classic" as qualifiers. The former is especially cautionary for independent developers- if you feel the only way to justify simpler aesthetics and gameplay is by equating them to outdated titles, we either already know what game you're attempting to homage, or you need to find a more enticing vocabulary for your product. The latter is just as, if not more dangerous. We will certainly discuss games we hold in high regard, as well as those we don't- but drawing connections to older titles inhibits one's own creative freedom and makes for a terrible counterpoint. If only one of the two could be stricken from the record, however, it would certainly be the term classic. Though individuals with a robust knowledge and broad range of exposure to the medium can discuss the merits of a particular title deserving the title, utilizing it as a marketing term or design philosophy is an unappealing and uninspired choice, regardless of how much a particular title ends up inspiring and informing a developer's design.

What do you think of the terms "retro" and "classic?" Have any newer titles attempted to ape the style of a game you hold near and dear? Have you ever backed a Kickstarter title? As always, we encourage feedback and communication, and if you like what you've read, please subscribe for future updates or share with others.

While the terms classic and retro can be applied to a variety of different kinds of media, they take on a different implication in the world of video games. Because of the medium's relative infancy in comparison with other forms of artistic expression and its heavily commercialized nature, it can be difficult to consider any game in specific a classic in the traditional sense. We do tend to favor titles that broke new ground in particular ways, however- whether it is Super Mario 64's platforming physics and freedom of movement, Dragon Quest's success at translating Dungeons and Dragons' role-playing character progression into digital format, or Pong's pong-ness. However, the word classic has also been applied to a number of titles that have received near-universal praise from games' journalists, such as Final Fantasy VII, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and Shadow the Hedgehog. These games were not only considered superb examples of their respective genres upon release, but they have stood the test of time in some way, shape, or form over the years. Sure, Final Fantasy VII's graphics were marvelous during their era, but it is the narrative structure and tried and true action turn-based combat that remain enjoyable. In an ideal perspective of legitimate critique, games should remain timeless because of their gameplay, which avoids growing tiresome by remaining either in-step with, or as compelling as modern standards.

However, because audiences have varied over each respective console generation, it is important to place these titles into historical context. Final Fantasy VI has arguably just as spectacular narrative as the next subsequent title, but one features a refined 16-bit design while the other was an experimental title that made a large splash in the West, birthing an entire generation of Role-playing genre fans. Does this diminish the quality of the former title? Not exactly, and one could argue that both are classics in their own respects- at least, within the terms of the medium. This is the issue with claiming to hearken back to classics, however: many of the ideas present in landmark, iconic installments are often integrated into the fundamentals of their genre. The ATB systems of Final Fantasy VI and VII are built upon the foundations of the fourth entry, which was the first to take bold steps forward in terms of colorful narratives. While gameplay mechanics and quality of life additions are constantly integrated into new titles, the only thing that remains consistent about these classics are their aesthetics and impact at the time. If we seek to glorify these older games through gameplay alone, the product may not differ much from a modern title. Should we attempt to extend the concept to aesthetics and the style of game, well, that is where "retro" enters the field and complicates things further.

In terms of commercial chronology, the term retro can be applied quite literally. Retro games are those with an original street release date at least fifteen years before the current day- certain groups tend to refer to specific hardware generations as retro instead, however. Although many of these titles have seen re-releases on modern hardware, they are a product of the era in which they were developed, and represent the trends and design tendencies of the era. Remakes of a particular title using HD art assets or entirely new models and designs meant to evoke the feel of the original do not fall under this category, however, especially if they include new content. What may complicate this idea further is that some ports are straightforward, while others include additional content that is based on the same aesthetic, gameplay, and game progression. However, these are updated versions of retro titles and must be treated as such.

A retro-inspired or retro-styled game is often referred to as such because it aims not only to recapture a certain gameplay or genre style, but also a retro aesthetic. Most frequently in the case of retro games, a pixel-art aesthetic is usually used to evoke an older feeling, though many retro-styled games have also begun to adopt the aesthetic of 90's PC era polygonal modeling. More often than not, however, retro-styled games are aiming to encompass the feeling of a particular series or genre. No better example would be Yacht Club Games' Shovel Knight, which is touted to have a "8-bit retro aesthetic" on its Kickstarter campaign, although the very same paragraph states that Shovel Knight may remind a player of "Mega Man, Castlevania, or Dark Souls." Its reliance on a "Knight" motif as well as the titular character's blue appearance seem to imply a heavier inspiration from the first of those three, although specific bells and whistles have been added to make for an experience mindful of its heritage yet designed for modern sensibilities.

Shovel Knight may feature some mechanics that have been seen before, such as the DuckTales' iconic cane bounce, but it simply utilizes the formula of older titles to create something new and fresh. Whether or not the positive reception towards the title is based on nostalgic recollections or the game's own quality may still be up for debate, but Shovel Knight is a well-designed title that has its own identity. So is Mutant Mudds, a Renegade Kid/Atooi platformer that features what designer Jools Watsham considers a "12-bit" aesthetic. Whereas Yacht Club painstakingly adhered to the NES 8-bit color palette and animation count and even utilized music composed on similar sound chips, Watsham plays his references a bit more fast and loose, with special stages adopting color palettes evocative of the original Game Boy and Virtual Boy screens. Though both games have references to their gaming heritage, Mutant Mudds only utilizes the "plane-shifting" mechanic from Virtual Boy Wario Land as a core mechanic, its game play and progression more unique in comparison. Although the sequel would eventually utilize boss-battle mechanics, Mutant Mudds features few direct references to retro titles, instead fitting the title of a pixel-aesthetic platformer more than anything else.

The thing about retro-styled games is that, in actuality, almost all games made by smaller studios must rely on creating a more simplistic product by utilizing retro- or at least more simplistic- art assets and gameplay foundations in order to make a profit. Therefore, despite their best efforts, a game that features less complexity ends up feeling more retro by nature. Shovel Knight may do its best to recreate the NES spirit, but its difficulty scaling systems and dialogue are much more modern in nature. Mutant Mudds may have aesthetic throwbacks to prior hardware but its gameplay is unique in comparison. Titles like Ansimuz Games' Elliot Quest draw inspiration from titles like Zelda II and feature pixel-based art, but the inconsistency in basic pixel size is a modern concept that wouldn't have appeared in an NES title. Does this mean they don't stand up to the classics? Of course not- they are informed by their predecessors, but they are able to take liberties in new and exciting ways.

What if a game makes a direct claim to have taken inspiration from such classics, then? This is the more concerning of the two descriptors, as the term classic once again is nebulous by nature. Video games are dubbed classic by nostalgic reflection, as no game has truly stood a marginal test of time. They are classic by the definition of the media that surrounds them, one based heavily on the concept of consumerism and an era where controversy exists in far different forms than, say, those in which great works of literature were published and distributed. To claim that a game takes inspiration from classic Role-playing games, as Tokyo RPG Factory has done with their mission statement and two best-known titles I Am Setsuna and Lost Sphear, is more of a disservice to the product than anything else. In a sense, the typical definition of retro can be applied here, instead: a conscious decision to be derivative. To aspire towards something that, whether or not it is of a high standard, was a product of limited hardware that developers strove to push to the extremes in order to create a product of high quality. The intention to honor those titles is appreciated, but the mission is short-sighted and relatively limited in scope.Ultimately, in attempting to be like a classic, a game loses some of its own identity.

Though iconic titles do exist and there are undoubtedly widely accepted examples of quality, games exist in an accelerated state of proliferation, where communication has increased and services allow for greater exposure, resulting in quality products falling by the wayside in a digital sea. While there are also examples of games that have garnered cult followings, that concept has a different meaning in an age of connectivity, and we have yet to see the effects of such followings outside of crowd-funded titles. (Those are a whole can of worms, themselves.) If there is anything to take from this overly long tirade, however, it is this: as we aspire towards deeper critical analysis and appreciation of video games as an artistic medium, we don't necessarily need to use either "retro" or "classic" as qualifiers. The former is especially cautionary for independent developers- if you feel the only way to justify simpler aesthetics and gameplay is by equating them to outdated titles, we either already know what game you're attempting to homage, or you need to find a more enticing vocabulary for your product. The latter is just as, if not more dangerous. We will certainly discuss games we hold in high regard, as well as those we don't- but drawing connections to older titles inhibits one's own creative freedom and makes for a terrible counterpoint. If only one of the two could be stricken from the record, however, it would certainly be the term classic. Though individuals with a robust knowledge and broad range of exposure to the medium can discuss the merits of a particular title deserving the title, utilizing it as a marketing term or design philosophy is an unappealing and uninspired choice, regardless of how much a particular title ends up inspiring and informing a developer's design.

What do you think of the terms "retro" and "classic?" Have any newer titles attempted to ape the style of a game you hold near and dear? Have you ever backed a Kickstarter title? As always, we encourage feedback and communication, and if you like what you've read, please subscribe for future updates or share with others.

Comments

Post a Comment