I'm not much of a Resident Evil fan- or at least, I wasn't, growing up. It was only the lack of titles present in the 3DS library that pushed me to pick up the technically astounding Resident Evil Revelaitons (not a typo) and begin to become somewhat enamored with the series. In truth, I was something of a skittish person in my youth, painfully aware of bumps in the night and checking behind my shoulder on many occasions. Horror games didn't really appeal to me, and even tense situations in games like Metroid Prime 2 would have me walking off nervous energy. I became a bit more familiar with the horror genre as I grew older, eventually accepting it and enjoying the thrill of my pulse pounding and discomfort rising during tense sequences. Still, it took me even more time to get into horror games, partially because I wasn't quite certain how these kinds of titles would attempt to replicate the staples of the cinematic and storytelling genre while still utilizing the unique features of the medium, itself.

I'm not much of a Resident Evil fan- or at least, I wasn't, growing up. It was only the lack of titles present in the 3DS library that pushed me to pick up the technically astounding Resident Evil Revelaitons (not a typo) and begin to become somewhat enamored with the series. In truth, I was something of a skittish person in my youth, painfully aware of bumps in the night and checking behind my shoulder on many occasions. Horror games didn't really appeal to me, and even tense situations in games like Metroid Prime 2 would have me walking off nervous energy. I became a bit more familiar with the horror genre as I grew older, eventually accepting it and enjoying the thrill of my pulse pounding and discomfort rising during tense sequences. Still, it took me even more time to get into horror games, partially because I wasn't quite certain how these kinds of titles would attempt to replicate the staples of the cinematic and storytelling genre while still utilizing the unique features of the medium, itself.As it turns out, it has a great deal to do with the economy of space, among other aspects.

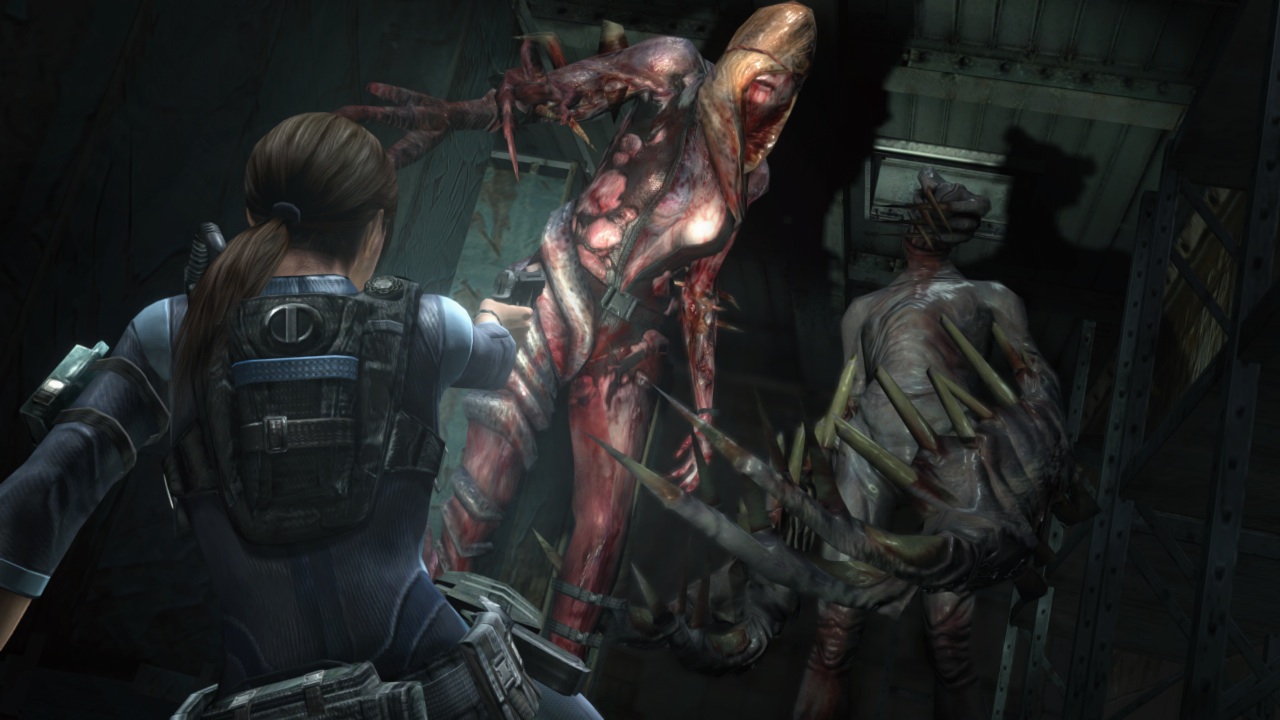

See, horror video games have the unique potential to make the player do something don't want to do in order to progress. The objective behind any game is to complete it, and games are able to have players reach an end state with or without a narrative intact, which only benefits the horror genre further. Horror requires specific rules in order to be convincing, but it doesn't need to follow a traditional narrative- in fact, fear of the unknown is one of the most effective kinds of fear, which is why games like Resident Evil benefit so much from placing stringent limitations on economy of space and resources. Having to conserve resources is a huge part of any Resident Evil title, at least, from their outset. Not knowing what will appear next, demanding attention and consuming what little you have managed to scrape together, is one of the more stressful aspects of the series' design. However, what is much more stressful is the tight spaces these games force upon the player. Coupled with the unknown nature of their narratives, each small room in a Resident Evil game oppresses the player, as every enemy present within that area serves as an active hazard that can impede process.

This is why the best Resident Evil player has a keen understanding of their surroundings- aware of what obstacles might halt or slow their movement, and how much space they really have in order to get where they need to go. This is also why these titles offer plenty of shortcuts and side-routes in their more open areas, allowing for players to maximize the mindless movement options of their pursuant in order to avoid a grisly fate. In a tense situation, a player needs to know what they have available to them, which is why the lack of resources adds another level of stress to each scenario. The feeling that options are limited is a type of claustrophobia, and its the horror element that is the easiest to capture in the video game format. In their opening moments, horror games often have an innate feeling of the unknown, a lack of understanding, but because of their nature, a player can slowly and efficiently adapt to this feeling. This is why many recent Resident Evil titles, particularly those preceding the seventh entry, had a gradual amplification of conflict and simultaneous descent into absurdity. The feeling of the unknown, and the tension that matches it, is ultimately fleeting, especially in a medium where retries are essential and learning is an inherent part of the process. What better way to perpetuate a sense of tension then by upping the stakes with increasingly ridiculous scenarios?

Well, as it turns out, there are plenty of other ways to do so- some of them just as good, if not better, than the Resident Evil action philosophy. But we'll have to cover them at a later date, as I'm currently getting the snot beaten out of me in Resident Evil Revelations 2.

Comments

Post a Comment